6.29.2006

The News

Every morning, as I leave the “estate”, I pass a newspaper seller, who spreads the day's papers out on a burlap sack and pins them down with stones. There is always a group of people crowded around, reading the headlines of the 5 English-language dailies, and occasionally forking out a few shillings to walk away with a copy of the day’s news. At my house, the TV is tuned to the BBC news round up in the morning, Swahili News at 7 and the English News at 9 without fail. Dominating the news since I arrived has been the case of the Artur brothers, two Armenians who were hastily deported after some sort of showdown at the airport, but who may be recalled to testify before a congressional commission if a presidential commission doesn’t declare the congressional commission unconstitutional because the president’s office may have been a little too buddy buddy with the Armenians who may or may not be arms traffickers and who may or may not come back anyway so that one of them can marry the Kenyan love of his life. I think.

In Tanzania, the Swahili papers were primarily gory photos of bus accidents, tabloid photos of girls in small outfits acting sloppy, and accusations of witchcraft between the two best soccer teams. The English language paper was almost unreadable and certainly did little to advance public interest. Here, the papers are mostly dominated by political news, but they also publish Reuter’s reports from around Africa, and have pretty intelligent editorials and even some arts and living pullouts and kids’ sections. The television news is decent too, even doing stories on the plights of some of the poorest communities who have been displaced by development or, in the northwest, by conflict.

The most exciting thing about the news here is that everyone is engaged, and you can hear people arguing politics in every public place. I get the sense that everyone is fed up with corrupt and self-serving leaders, and tired of living in a dysfunctional country as a result of it. And they are certainly willing to say so. Five years ago, Kenyans were living under a blatantly corrupt ruler finishing his 25th year in office and this month the members of parliament had to cut back some of the benefits they had lavished on themselves. Now, will Kenyans be able to translate their outrage into action to fundamentally change the way their government works? I am excited to find out.

In Tanzania, the Swahili papers were primarily gory photos of bus accidents, tabloid photos of girls in small outfits acting sloppy, and accusations of witchcraft between the two best soccer teams. The English language paper was almost unreadable and certainly did little to advance public interest. Here, the papers are mostly dominated by political news, but they also publish Reuter’s reports from around Africa, and have pretty intelligent editorials and even some arts and living pullouts and kids’ sections. The television news is decent too, even doing stories on the plights of some of the poorest communities who have been displaced by development or, in the northwest, by conflict.

The most exciting thing about the news here is that everyone is engaged, and you can hear people arguing politics in every public place. I get the sense that everyone is fed up with corrupt and self-serving leaders, and tired of living in a dysfunctional country as a result of it. And they are certainly willing to say so. Five years ago, Kenyans were living under a blatantly corrupt ruler finishing his 25th year in office and this month the members of parliament had to cut back some of the benefits they had lavished on themselves. Now, will Kenyans be able to translate their outrage into action to fundamentally change the way their government works? I am excited to find out.

6.21.2006

Any other names

I wrote previously about the Kikuyu system of naming, but I recently learned about the Luo system for last names, which I think is even better because it is completely random. Basically, you get your last name based on what time of day you were born. I’m not up on the literature, so I don’t know if being born at certain times runs in families, but essentially, if you were born in the afternoon you get a certain last name, and if your sister was born late at night, she gets a different one. If you are a girl, it starts with a, but if you are a boy it starts with o, and that’s it.

First names are funny too; most of them are Anglo but pretty old-fashioned so that all the women sound like 1950s housewives—Phyllis, Eunice, Gladys, and Beatrice are all popular. I wonder if these are the names that missionaries and colonists had and handed out, and what happened to the names that babies used to get.

First names are funny too; most of them are Anglo but pretty old-fashioned so that all the women sound like 1950s housewives—Phyllis, Eunice, Gladys, and Beatrice are all popular. I wonder if these are the names that missionaries and colonists had and handed out, and what happened to the names that babies used to get.

Traveling companions

I have a small confession to make. During the school year, I used to get annoyed when I would hear that yet another person from my school was also going to be in Kenya, and when they would talk about meeting up or traveling around, I would sort of yeah, whatever them and think to myself that I would be much too hip to the East Africa thing and much too busy with my work and with spending time to Kenyans to spend time hanging out with them.

But that was stupid. I forgot how when you’re in a foreign country you want to see everything and go everywhere. And I forgot how much more fun it is to see things with other people who are also excited to be in the country and also excited to see things. And most of all, I forgot how cool the people I go to school with are. So here’s a picture of me with some of the cool people I am lucky to get to hang out with this summer.

But that was stupid. I forgot how when you’re in a foreign country you want to see everything and go everywhere. And I forgot how much more fun it is to see things with other people who are also excited to be in the country and also excited to see things. And most of all, I forgot how cool the people I go to school with are. So here’s a picture of me with some of the cool people I am lucky to get to hang out with this summer.

Heard from a hill in Homa Bay

The first hill we climbed, and the town of Homa Bay.

It is Sunday, a day off, so a group of us goes exploring around the town of Homa Bay. The town has these steep hills like the tips of volcanoes poking through the earth, so we clamber up one. On top we catch our breaths, sweat drying in the breeze, and we take in the panorama. It is a great view, with Lake Victoria shimmering silver, green shores in a haze in the distance. At our feet are the rusting roofs of houses in Homa Bay and to the West, neat, green fields as far as the eye can see. We also spot another hill, right on the water, that looks like it will have a great view of the lake.

We guess our way to the base and then ask a lady selling tomatoes how to get up. The path is gravelly and slippery, and occasionally weaves around places where big boulders have been scooped out. The bushes eventually get too thick and too thorny for me and I sit in the shade as my companions brave the jungle to the top. At the base of the hill a husband and wife are working. He breaks the boulders from the hill into appropriate sized stones for building—chink chink chink—and she carries the stones down the hill in a burlap bag on her head. It is noon on Sunday, and as we sweat and suffer for the exercise and for the view, this is what they are doing.

A brown and white sheep wanders by. Near me on the hill, I hear her bleating, the clicks of grasshoppers, chirping birds, and the sounds of the rock breaker. From below, the sounds of life waft up—rumbling trucks, babies crying, roosters crowing, and the dueling loudspeakers of a chanting imam and a fire and brimstone preacher. The lake, to my right and behind the hill, is silent, mute dhows plying its surface. Also silent, sorghum ripening in the field, the dogs asleep in the shade, the red dust rising, and butterflies, which have overrun the town of Homa Bay.

A girl thing?

So I’ve been having this ongoing conversation with different people about the gender ratio in Kenya. On several occasions, I have been informed that there are four women for every man in Kenya. This has been repeated to me by uneducated and educated Kenyans and even by one American expatriate. I have heard it expressed as a percent, I have heard supporting information (i.e. that 75% of newborns are female) and everyone I have talked to insists that it is true, though no one can explain why it would be. I am willing to buy that men die more quickly here of HIV and from violence and accidents, and I think it might even be possible that women outnumber men, particularly in the older age brackets. But if an entire nation were so dramatically skewed, I promise you, the world would be hearing about it. If girls were being born three times more frequently than boys, we would know about it. As it is, in Kisumu town, men are everywhere, most of them zipping around or lounging on bicycle taxis, offering to take you anywhere in town for 15 cents.

Having this conversation, though, and appreciating the persistence of that particular statistic has made me wonder about some of the myths we pass around in America. That people of different races all have equal opportunities might be one of them, that being thin denotes being healthy, that children raised in non-nuclear families are inherently worse off, that our government is an expression of the will of the people. I’m sure there are others—the lies that stick in peoples minds and mouths despite all evidence that contradicts them.

Having this conversation, though, and appreciating the persistence of that particular statistic has made me wonder about some of the myths we pass around in America. That people of different races all have equal opportunities might be one of them, that being thin denotes being healthy, that children raised in non-nuclear families are inherently worse off, that our government is an expression of the will of the people. I’m sure there are others—the lies that stick in peoples minds and mouths despite all evidence that contradicts them.

6.12.2006

At last! Pictures!

Well, this is all I could eke out from the internet connection, I'll try to post more later.

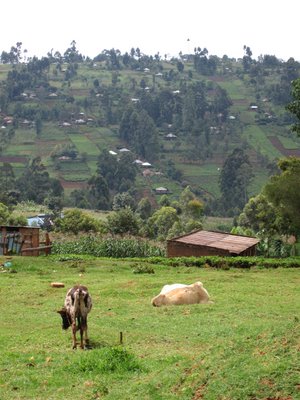

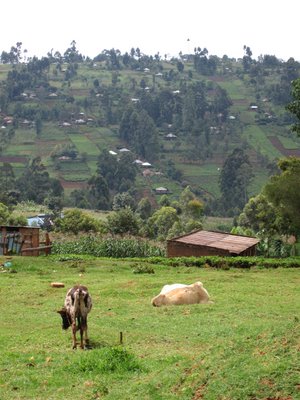

Fields near Nyamira.

Kisumu town at dawn.

Fields near Nyamira.

Kisumu town at dawn.

Dancing the Hungula

To dance the Hungula, first you have to find where a band is playing. Electric keyboard, drums, shakers, a clanging metal ring, and vocals sung through enormous, low-quality speakers. Then you watch them warm up, playing songs with no vocals as you sip your soda or your beer. Then, once the singer takes the stage, and the crowd gets big enough, and you, being the only white person there, get your nerve up, you’re ready for the dance floor.

So you bend your arms at the elbow and flap them up and down or move them like you’re running, but keep your shoulders pretty still. The step, if you choose to do one at all, is left-right-left-right and you can do it on every beat or every other beat, or some combination thereof. Then you move your hips, as much or as little as you want, and you’re dancing the Hungula! You can dance by yourself, or in a group, or with a partner. Your Luo counterparts laugh at the lyrics to the songs and point out the other people you are dancing with—politicians, prostitutes, and other scandalous personalities of Kisumu’s elite. The old guys have big bellies but still like to gyrate like salamanders, and the married women dance with each other, looking respectable. The women have all had their hair done, but their clothes range from T-shirts and jeans to evening wear with sequins. The men wear loud shirts and pants that balloon at the hip and taper at the ankle. It’s raucous but relaxed, a great form of exercise, and a very fun evening.

So you bend your arms at the elbow and flap them up and down or move them like you’re running, but keep your shoulders pretty still. The step, if you choose to do one at all, is left-right-left-right and you can do it on every beat or every other beat, or some combination thereof. Then you move your hips, as much or as little as you want, and you’re dancing the Hungula! You can dance by yourself, or in a group, or with a partner. Your Luo counterparts laugh at the lyrics to the songs and point out the other people you are dancing with—politicians, prostitutes, and other scandalous personalities of Kisumu’s elite. The old guys have big bellies but still like to gyrate like salamanders, and the married women dance with each other, looking respectable. The women have all had their hair done, but their clothes range from T-shirts and jeans to evening wear with sequins. The men wear loud shirts and pants that balloon at the hip and taper at the ankle. It’s raucous but relaxed, a great form of exercise, and a very fun evening.

6.10.2006

Kicks in Kenya

My time in Kenya so far has been a week-by-week progression from big city to medium town to small town. I started in Nairobi, a city where crime is so pervasive (or the fear of it is, at least), that I found myself shuttled from guarded enclave to guarded enclave—CDC office, my friend's hotel, expat-frequented restaurants. It was hard to get my bearings and hard to feel like I was somewhere new. My first Sunday I got to tag along with a Kenyan family as they went to their family farm just outside the city. It was a special occasion because a grandchild had just been born and was coming home from the hospital. As the first daughter, she was named after the father's mother and had to pass through her grandmother's house before she went home. Evidently, for Kikuyu people, there are strict rules about what to name each child—the first daughter after the father's mother, the second after the mother's mother, then on to the parents' brothers and sisters. The family conversed in English, Swahili, and Kikuyu there were maybe twenty people there, and all the kids the same age had the same names, which added to the general confusion. Also there was the new baby's great-grandmother, a woman of nearly 100 with dangling stretched earlobes. Apparently, she is a bit senile, but if she could remember everything that's happened in the last 100 years, that would be amazing. I congratulated myself on working my way through a heaping plate of food at 3 in the afternoon, but just as I was taking my last bites a bowl full of roasted goat meat was placed before me and I had to incur the profound disappointment of the grandmother who asked me, wasn't the food alright?

And then I decamped to Kisumu, my home base for the next 8 or so weeks. I didn't know anything about the town except that it is on Lake Victoria. It's actually very lovely—the downtown is comprised of white two and three story buildings and is overrun with bicycle taxis. At the shore, there is a row of tin shacks serving huge fish that are deep-fried whole and served with tomato sauce, greens, and ugali (stiff corn porridge), one of the most delicious meals I have ever eaten. I found a place to live with a family in a Kenyan version of a gated community—paved streets in a neat grid, house numbers, and the "estate" has a school, a soccer field, and a small pub. The funny thing is that there isn't any visible extra security, just one gate that is unguarded and always ajar. Yet somehow the imposition of order keeps the usual African chaos at bay. Or maybe I'm missing something. My host mother, Florence, is a nurse from the TB ward at the provincial hospital and she invited me to live with her "African-style". She promised that I would only have to share a room with her 7 year old daughter, but the other day I looked over and the bed next to mine had 4 people in it. I suppose a better person than I would have offered to share, but, let's be real, I need my beauty sleep.

And then this last week I made a trip to the small town of Nyamira. I knew nothing about the place except that the district hospital was one of the sites that the people at the head office wanted me to look at. It is up in the hills and from the guesthouse there is a gorgeous view of the valley below, a green patchwork of small farms, mostly growing tea. The other afternoon, it rained and you could see it coming from the opposite hill, the shopkeepers packing up their wares as the first fat drops fell. The town itself consists of some general shops lining a single road, trafficked primarily by pedestrians, and there is no internet or restaurant anywhere. Still, at night, the bar across the street was blasting Congolese music and it sounded like plenty of people were there having a good time.

And there is the project I am doing. Basically, this province has a very high prevalence of HIV, and the prevalence is even higher among expectant mothers (20-30%). Most of these women attend some form of prenatal care, so that is a really important time to make sure they get tested for HIV to prevent transmission to the baby and to provide the mother with care. There are different ways that facilities are trying to follow up with HIV-positive pregnant women, so I am going to three of these to compare how their programs are working. The hospitals record all their data on paper (the one I was working at is the largest in the district and has a grand total of 2 computers for the whole facility) so I found myself entering data into my laptop in various wards while trying not to be distracted by the screams of babies being vaccinated, women giving birth, and one very disgruntled cow in the field beside the records office. The worst part about the project is seeing how under-resourced the health workers are, and then knowing that I have to bother them in order to make my project happen. Instead of feeling like I am doing something helpful, I can see that my project actually has a direct negative impact on patient care. To assuage my guilt, I attended a meeting of an AIDS patients club to offer moral support. As I should have expected, I was treated like the guest of honor, and ended up blathering about human rights in Swahili for a good chunk of time, as if those poor people hadn't suffered enough.

I have to say that traveling like this, with a task, can be a lot more interesting than pure tourism, even though I am only here for a relatively short time. In addition to that ridiculous speech, I got to play and sing with a group of HIV-positive toddlers at another hospital and to attend a soccer practice for a team of boys from Kisumu's largest slum. I have been invited for dinner at several houses and I just feel much more connected to the places I've been. It's not really about authenticity, because I know that I am still in Kenya's little public health world, but about actually being here, instead of feeling like I am just passing through. Kenya is great, and I'm having a really good time.

And then I decamped to Kisumu, my home base for the next 8 or so weeks. I didn't know anything about the town except that it is on Lake Victoria. It's actually very lovely—the downtown is comprised of white two and three story buildings and is overrun with bicycle taxis. At the shore, there is a row of tin shacks serving huge fish that are deep-fried whole and served with tomato sauce, greens, and ugali (stiff corn porridge), one of the most delicious meals I have ever eaten. I found a place to live with a family in a Kenyan version of a gated community—paved streets in a neat grid, house numbers, and the "estate" has a school, a soccer field, and a small pub. The funny thing is that there isn't any visible extra security, just one gate that is unguarded and always ajar. Yet somehow the imposition of order keeps the usual African chaos at bay. Or maybe I'm missing something. My host mother, Florence, is a nurse from the TB ward at the provincial hospital and she invited me to live with her "African-style". She promised that I would only have to share a room with her 7 year old daughter, but the other day I looked over and the bed next to mine had 4 people in it. I suppose a better person than I would have offered to share, but, let's be real, I need my beauty sleep.

And then this last week I made a trip to the small town of Nyamira. I knew nothing about the place except that the district hospital was one of the sites that the people at the head office wanted me to look at. It is up in the hills and from the guesthouse there is a gorgeous view of the valley below, a green patchwork of small farms, mostly growing tea. The other afternoon, it rained and you could see it coming from the opposite hill, the shopkeepers packing up their wares as the first fat drops fell. The town itself consists of some general shops lining a single road, trafficked primarily by pedestrians, and there is no internet or restaurant anywhere. Still, at night, the bar across the street was blasting Congolese music and it sounded like plenty of people were there having a good time.

And there is the project I am doing. Basically, this province has a very high prevalence of HIV, and the prevalence is even higher among expectant mothers (20-30%). Most of these women attend some form of prenatal care, so that is a really important time to make sure they get tested for HIV to prevent transmission to the baby and to provide the mother with care. There are different ways that facilities are trying to follow up with HIV-positive pregnant women, so I am going to three of these to compare how their programs are working. The hospitals record all their data on paper (the one I was working at is the largest in the district and has a grand total of 2 computers for the whole facility) so I found myself entering data into my laptop in various wards while trying not to be distracted by the screams of babies being vaccinated, women giving birth, and one very disgruntled cow in the field beside the records office. The worst part about the project is seeing how under-resourced the health workers are, and then knowing that I have to bother them in order to make my project happen. Instead of feeling like I am doing something helpful, I can see that my project actually has a direct negative impact on patient care. To assuage my guilt, I attended a meeting of an AIDS patients club to offer moral support. As I should have expected, I was treated like the guest of honor, and ended up blathering about human rights in Swahili for a good chunk of time, as if those poor people hadn't suffered enough.

I have to say that traveling like this, with a task, can be a lot more interesting than pure tourism, even though I am only here for a relatively short time. In addition to that ridiculous speech, I got to play and sing with a group of HIV-positive toddlers at another hospital and to attend a soccer practice for a team of boys from Kisumu's largest slum. I have been invited for dinner at several houses and I just feel much more connected to the places I've been. It's not really about authenticity, because I know that I am still in Kenya's little public health world, but about actually being here, instead of feeling like I am just passing through. Kenya is great, and I'm having a really good time.

What the HIV clinic is like

I spent several days this week at one of the better “Patient Support Centers” in Western Kenya. They are called that because other places have found that calling it an “HIV clinic” deters people from coming. Supported by the government and several NGOs, this particular clinic offers free medications including multivitamins, treatment for opportunistic infections, and as of June 6, antiretrovirals. The place has been recently refurbished and the waiting room is private. So this is one of the better places around for people with HIV to go for care.

But the atmosphere can be grim. People who are coming for follow-up visits often look unhapphy and anxious not to be seen, even if they are still healthy. Many of the people at the clinic are arriving for the first time—they have been admitted in the ward for some illness and the doctor recommended they be tested, or they had a persistent cough and have now been diagnosed with TB and HIV on the same day. Or, for the women I am trying to learn about, they came to the hospital for a routine prenatal visit and now their world has been shattered. All of these people have the shell-shocked and sheepish expressions of people that have just been thrown into a stigmatized group and handed what is still a death sentence at the same time. The people who come in sick are the worst, they are ashamed of their ill health, and some of them look like they expect to die. They register at the front desk and then they wait to see the doctor. Since the patients are many and the doctor is only one, they wait a long time.

But this clinic has a program of peer escorters--HIV infected volunteers at the clinic to show people where the lab is, to accompany people who have just been diagnosed, and to help with routine tasks like opening files. There is also a long-term Japanese volunteer who speaks Swahili (which, oddly, she and I used as our common language). These volunteers and the nurses maintain a banter that is noisy and cheerful, and make the clinic seem like more of an ordinary, lively place and not as much a house of death.

Then, too, there are patients like the baby I saw, her face covered with sores, her eye swollen shut and too lethargic to fuss, and no one could laugh when they saw her.

But the atmosphere can be grim. People who are coming for follow-up visits often look unhapphy and anxious not to be seen, even if they are still healthy. Many of the people at the clinic are arriving for the first time—they have been admitted in the ward for some illness and the doctor recommended they be tested, or they had a persistent cough and have now been diagnosed with TB and HIV on the same day. Or, for the women I am trying to learn about, they came to the hospital for a routine prenatal visit and now their world has been shattered. All of these people have the shell-shocked and sheepish expressions of people that have just been thrown into a stigmatized group and handed what is still a death sentence at the same time. The people who come in sick are the worst, they are ashamed of their ill health, and some of them look like they expect to die. They register at the front desk and then they wait to see the doctor. Since the patients are many and the doctor is only one, they wait a long time.

But this clinic has a program of peer escorters--HIV infected volunteers at the clinic to show people where the lab is, to accompany people who have just been diagnosed, and to help with routine tasks like opening files. There is also a long-term Japanese volunteer who speaks Swahili (which, oddly, she and I used as our common language). These volunteers and the nurses maintain a banter that is noisy and cheerful, and make the clinic seem like more of an ordinary, lively place and not as much a house of death.

Then, too, there are patients like the baby I saw, her face covered with sores, her eye swollen shut and too lethargic to fuss, and no one could laugh when they saw her.

More mundane

So I realize that in my dispatches I tend to forget to include the more mundane aspects. So, in addition to the fun and exciting adventures I've been having:

I fell down (yes, again) and scraped my knee and so now have a big scab that everyone seems to need to comment on.

I have to buy a new toothbrush because of an encounter with my old friend, the African cockroach.

When I got on the bus to Kisumu, they had some security officers with handheld metal detectors. Since I am carrying laptop, camera, taperecorder, cellphone, and various plug convertors, I set it off about 14 times. However, since I am also trying not to look like The Perfect Robbery Victim I declined to open my bag in the middle of the bus station, and so just whispered in the guard's ear what each beeping was and asked her to believe me that they weren't weapons. She did.

I fell down (yes, again) and scraped my knee and so now have a big scab that everyone seems to need to comment on.

I have to buy a new toothbrush because of an encounter with my old friend, the African cockroach.

When I got on the bus to Kisumu, they had some security officers with handheld metal detectors. Since I am carrying laptop, camera, taperecorder, cellphone, and various plug convertors, I set it off about 14 times. However, since I am also trying not to look like The Perfect Robbery Victim I declined to open my bag in the middle of the bus station, and so just whispered in the guard's ear what each beeping was and asked her to believe me that they weren't weapons. She did.

6.01.2006

Prenatal Care in Kisumu town

I spent a recent afternoon in the public hospital in Kisumu. The hospital is a complex of small buildings set in a grassy space, and it is the best cheap option in town. We started at the administration office, a perceptibly decaying building at the back of the complex. The head administrator’s office had a tiny waiting room presided over by a secretary with a manual typewriter. The maternal and child health clinic had a room smaller than my living room, jammed with mothers holding sick babies and children. In this room, the babies were weighed, vaccinated, and seen by the one doctor.

The worst was the maternity wards. There was one room for women in labor and women with complicated pregnancies, which was full of patients and their family members. There was a non-sterile theater for deliveries, and then another room for women who have delivered. The nurses told me that the bed shortages are so acute that they keep women for about 6 hours only after delivery, and that sometimes women who have had caesarean sections or who have just delivered have to share a bed. It makes you understand why 60% of women here deliver at home.

The best, most impressive thing about the hospital was the determination and caring of the staff. They all obviously knew and felt bad that they were not providing a high enough standard of care. All of them have insane workloads, and despite the fact that this hospital now has HIV treatment and medicines for preventing mother to child transmission, they are missing other essential supplies and their patients often can’t afford to buy the prescriptions or follow the advice that the doctors give them. At the public hospitals they work longer hours and are paid less than at private. So many of them burn out on patient care, and if they are well-connected, they find a position in the private sector, or an administrative role for an NGO or aid agency or in another country. They know that they are needed at the bedside but without support, the task is too hard and the sick patients are too many. Without enough resources, patients will never be well served.

Hit Counter